Project: Jungwon National Research Institute of Heritage

Credit: poly.m.ur Ltd. (Hongsik Kim, Homin Kim)

Design Team: Heekyung Mun, Sangki Lee, Sunmun Kim, Juyoung Choi, Suki Kwon, Seokyoon Kim, Jongcheol Lee, Sunki Whang, Jaeho Song

설계: 김홍식, 김호민

설계담당: 문희경, 이상기, 김선문, 최주영, 권숙희, 김석윤, 이종철, 황선기, 송재호

구조설계: 서진구조

기계설계: 우진설비

전기설계: 건창기술단

지질조사: 천지지하개발

토목설계: 동남이엔씨

목구조 설계·시공: 경민산업

견적: 신우건축

시공: 허밍건설

감리: 삼우 CM

자문: 윤홍로(문화재위원), 김영태(영남대학교)

건축주: 문화재청

중원은 충주를 중심으로 신라, 백제, 고구려가 각축을 펼쳤던 지역으로 삼국의 특성이 모두 표출되는 중부 문화권을 뜻한다. 2010년 중원 지역 문화재의 지속적인 발굴과 연구, 유물의 보존을 위해 2 천 평 규모의 중원 문화 출토 유물 보관센터의 건립을 위한 현상설계에 참여하여 당선되었다.

중앙의 국립 문화재 연구소를 포함하여 현재까지 전국에 지어진 문화재 연구소는 총 다섯 개이다. 가야, 경주, 나주, 부여와 마지막으로 중원 연구소인데 이들 중 한옥의 지붕 양식을 직접 차용한 경주의 경우를 제외하고는 모두 현대 건축물이다. 이 때문에 문화재 연구소의 정체성을 보여줄 수 있는 건축에 대한 요구가 문화재청 내부에 팽배해 있었다. 한편 우리나라에서 활동하는 건축가로서 시대에 따라 양식이 확연히 달라진 현재에 전통과 연결시켜 정체성을 확보하려는 시도의 위험을 잘 알고 있었다. 이것은 큰 도전이었고 건축가로서 성취해보고 싶은 대 주제이자 과제기도 했다. 과연 한국적인 건축이란 어떤 것일까? 굳이 양식을 차용하지 않으면서 우리 건축의 정체성을 찾을 수 있는 것일까? 문양이나 색, 스타일을 베끼는 직접적인 방식을 지양하고 추상적으로 접근할 수 있는 방법에 대해 고민했다.

과거에 우리는 외부의 힘에 의해 근대화가 진행되면서 전통과의 간극이 급속히 벌어졌고 그에 따라 전통과 현대의 경계도 뚜렷해졌다. 그런데 70 년대 들어 편향적인 민족의식을 고양시키기 위해 현대 건축에 전통 양식을 직접적으로 차용하는 시도들이 팽배해졌다. 심지어 한옥의 지붕과 공포를 콘크리트로 찍어내는 기술까지 발달하기도 했다. 그러나 이런 시도들은 국수주의에 편향된 자기 만족은 있었을 지 몰라도 과거는 더욱 고립되고 현재와의 연결고리는 되레 끊어지는 결과를 초래하고 말았다. 어차피 전통도 진화하고 끊임없이 변화하는 것인데 현대와 접목시키는 시도들은 좀더 현실적이고 생동감이 있을 필요가 있다. 이번 기회에 양복 정장에 상고머리를 올리는 방식을 지양하고 세련되게 추상화 시킬 수 있는 방법을 고민하려 했다.

한편 이를 위한 조형 원리를 찾는 것은 또 다른 도전이었다. 전통 문양이나 형태를 가장해 크기만 키운 괴물이 되지는 말아야 했기 때문이었다. 좀더 근원적이고 보편적이면서도 고전미에 가까운 것을 찾고자 했다. 지구라트나 장군총처럼 좀더 근원적이고 원시적인 것에 최대한 접근함으로써 전통과 연결하려 했다. 다행히 전통의 직접적인 차용을 피하고 근원에 가까운 조형 언어를 찾으려던 시도들이 발주처에서 좋은 평가를 받았다는 점은 고무적이었다.

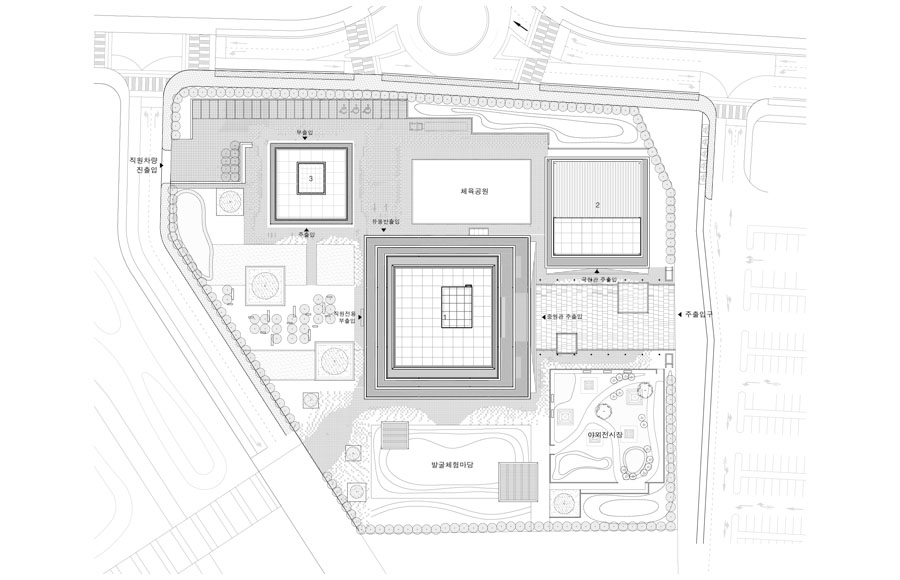

전체 연구소를 구성하는 세 개의 건물은 강당이 있는 국원관, 수장고 및 학예실 등 사무실 공간이 있는 중원관, 그리고 직원들의 기숙사 영역인 후생관이다. 규모는 각기 다르지만 모두 2 층이나 3 층 높이의 정방형 평면으로 구성되어 있다. 정방형 평면은 피라미드, 장군총 같은 묘나 석탑처럼 기념비적인 용도의 구조물에 많이 쓰인다. 그런데 이는 정작 우리가 자주 사용하는 건축에 적용하기 쉽지 않다. 그 이유는 규모가 큰 평면에 실들을 배치하다 보면 채광과 환기가 좋지 않은 방들이 어두운 중앙에 배치될 가능성이 높기 때문이다. 또한 주로 직사각형인 대지에 용적율을 다 채워서 계획하다 보면 결국 정방형의 평면을 적용할 수 있는 경우가 극히 드문 이유다. 중원연구소는 대지가 넓고 건폐율에 여유가 있을 뿐 아니라 채광을 필요로 하지 않는 수장고를 주 기능으로 하므로 정방형의 평면이 가능한 건축 유형이었다.

오랜 시간을 사무실에서 보내야하는 연구원들에게 좋은 사무 환경을 제공하기 위해 각 층마다 주위로 돌아가는 테라스를 계획했다. 넓은 터에 지어지는 연구소임에도 2 층이나 3 층에서 일하는 연구원이 바람을 쐬기 위해 1 층까지 내려가거나 옥상에 올라가야 한다면 불편하다고 생각했다. 한 두 층 오르고 내려가는데 무슨 큰 문제냐고 할 수도 있지만 분명히 이로 인해 번거롭게 되고 그러다 보면 결국 답답한 실내에서 하루 종일 시간을 보내야 하는 경우들이 생긴다. 마치 공원에서 일하듯 답답한 사무실에서 언제든 밖으로 나가 바람 쐴 수 있는 자유를 제공하고 싶었다. 흡연자들도 눈치 보지 않고 바깥 공기를 쐬며 담배 한대 피우고 다시 업무로 복귀할 여유를 갖기 바랬다. 아쉽게도 애초의 계획처럼 다양한 수목들로 채워지지는 못했지만 각 층의 사무실 주변을 돌아가는 잔디밭 테라스는 예상보다도 훨씬 더 호응이 좋았다. 밤낮과 주말도 없이 연구에 매진해야 하는 학예사들이 잠시 쉬는 쌈지 공원이자 환기가 필요할 때 문을 열기만 하면 시원한 바람이 들어오니 금상첨화다. 딱딱한 문화재 연구소에서 일하는 직원들에게 다소 숨통을 틔워주는 공간이 된 것은 가장 큰 수확이었다.

Jungwon refers to central region of the Korean peninsula that encompasses cultural identities of 3 ancient kingdoms of Korea- Shilla, Baekje, and Goguryeo- as it was a highly coveted and sought-after area. Design competition was held after it was decided to establish a research center dedicated to excavation, research, and preservation of cultural relics and artifacts in 2010, and poly.m.ur was awarded the project.

In addition to the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, Jungwon National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage would be the 6th national research institute of cultural research in addition to institutes already in place in Gaya, Gyeongju, Naju, and Buyeo. With an exception of the institute in Gyeongju, which adopted the design of traditional Korean roof, all other institutes were presented in a form of modern architecture. As they embarked upon the project of establishing the newest research institute, the Cultural Heritage Administration of the Korean Government was fully aware for the need to embrace Korea’s unique cultural identities to the design of architecture. Architects working in Korea know well the risk associated with attempts to bridge the past and present, and we also understood the challenge of defining an identity that translates the course of history into an architectural narrative with modern-day relevance. But it was a challenge that I had to take on; gladly and willingly. How do you define Korean architecture? Can the identity of Korean architecture be defined without adopting associative forms? I began the project by contemplating ways that would allow me to pursue abstract approaches to the design without having to resort to cliché characteristics such as patterns, colors, or styles. Korea’s rapid modernization is characteristically powered by foreign forces and resulted in rapid departure from the past with a clear division between the past and the present. When a manic wave of nationalistic movement swept the country in the 70s, architectural world responded by making literal adaptation of traditional forms to modern architecture. It was during this time when technology to churn out concrete tiles and capital for traditional roof designs was developed. Such attempts may have satisfied the nationalistic fever but ended up widening and deepening the gap between the past and present to a degree that the link was eventually severed. Like history that never stops and continues, tradition also evolves and changes. Therefore, attempt to embrace tradition should consider relevancy and vitality from modern point of view. I took this project as an opportunity to resist the urge to go on the same route of making literal adaptation of tradition as it would be like insisting traditional hair-style for a man dressed in suit. My sight was set on abstract and sophisticated interpretation of the Korean heritage. Next challenge that awaited me was figuring out the formative formula of my design vision that refused to create a colossal atrocity that pretended to embrace traditional shapes and forms. As I explored inspirations that were more fundamental and universal while being true to traditional aesthetics, idea of fundamental and primitive architecture such as ziggurat of ancient Mesopotamia and Janggunchong (Stone Tomb of General) gained strong support as an effective bridge to the past. Fortunately, my effort to come up with a formative narrative that focused on primitive inspiration without having to rely on superficial adaptation of cultural heritage was well recognized and received by the client.

The complex is designed to house 3 separate buildings: Gugwongwan with an auditorium, Jungwongwan with office spaces including storage and research facility, and Husaenggwan as dormitory for staffs. Varying in sizes, but each building adopted square shape for floor plan featuring 2 or 3 floors in height. Square floor plan is typically seen in monumental structures such as tombs – pyramids, Janggunchong, etc. - or stone pagodas. Its real-world application is limited, because it becomes inevitable for rooms placed in the middle to have limited access to light and air as more prominent rooms take the priority space near windows. Also, most properties are divided in rectangular shapes and effort to maximize the floor area ratio almost automatically rejects the concept of square-shaped floor plan. Application of square floor plan was possible for the Jungwon National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage because of 2 factors: generosity in the site area and applicable floor-area ratio and usage as storage space that didn’t require access to natural light.

For the main building of Jungwongwan where researchers were hard at work for long hours, terrace that encircles 3 sides was placed on each floor as an enhancement of work environment. Building wasn’t tall and it was only a floor or two to get fresh air from the ground floor or roof top, but it still didn’t seem unnecessary as long as there was enough space for alternative solutions. Outdoor space on each floor would be more effective in motivating the staffs to take the rest they need as it eliminates the trouble of leaving their floor. With such easy access to an outdoor space, there would be no excuse not to take advantage of the benefits and staffs could easily step outside and get fresh air as if their office is surrounded by a park. Smokers, in particular, would appreciate the layout. Original design of the terrace featuring a wide variety vegetation met with a setback and resulted in a more simpler landscape, but reception for the terrace garden was much more positive and enthusiastic than anticipated. Researchers were working in an intense environment often involving long hours and stressful situations, and they truly appreciated being offered an easy and simple access to fresh air just steps away from their office. Being able to create a space that was essential for the comfort and respite of researchers and staffs working in a rigid environment break was the biggest accomplishment of the project.

Credit: poly.m.ur Ltd. (Hongsik Kim, Homin Kim)

Design Team: Heekyung Mun, Sangki Lee, Sunmun Kim, Juyoung Choi, Suki Kwon, Seokyoon Kim, Jongcheol Lee, Sunki Whang, Jaeho Song

설계: 김홍식, 김호민

설계담당: 문희경, 이상기, 김선문, 최주영, 권숙희, 김석윤, 이종철, 황선기, 송재호

구조설계: 서진구조

기계설계: 우진설비

전기설계: 건창기술단

지질조사: 천지지하개발

토목설계: 동남이엔씨

목구조 설계·시공: 경민산업

견적: 신우건축

시공: 허밍건설

감리: 삼우 CM

자문: 윤홍로(문화재위원), 김영태(영남대학교)

건축주: 문화재청

Description

중원은 충주를 중심으로 신라, 백제, 고구려가 각축을 펼쳤던 지역으로 삼국의 특성이 모두 표출되는 중부 문화권을 뜻한다. 2010년 중원 지역 문화재의 지속적인 발굴과 연구, 유물의 보존을 위해 2 천 평 규모의 중원 문화 출토 유물 보관센터의 건립을 위한 현상설계에 참여하여 당선되었다.

중앙의 국립 문화재 연구소를 포함하여 현재까지 전국에 지어진 문화재 연구소는 총 다섯 개이다. 가야, 경주, 나주, 부여와 마지막으로 중원 연구소인데 이들 중 한옥의 지붕 양식을 직접 차용한 경주의 경우를 제외하고는 모두 현대 건축물이다. 이 때문에 문화재 연구소의 정체성을 보여줄 수 있는 건축에 대한 요구가 문화재청 내부에 팽배해 있었다. 한편 우리나라에서 활동하는 건축가로서 시대에 따라 양식이 확연히 달라진 현재에 전통과 연결시켜 정체성을 확보하려는 시도의 위험을 잘 알고 있었다. 이것은 큰 도전이었고 건축가로서 성취해보고 싶은 대 주제이자 과제기도 했다. 과연 한국적인 건축이란 어떤 것일까? 굳이 양식을 차용하지 않으면서 우리 건축의 정체성을 찾을 수 있는 것일까? 문양이나 색, 스타일을 베끼는 직접적인 방식을 지양하고 추상적으로 접근할 수 있는 방법에 대해 고민했다.

과거에 우리는 외부의 힘에 의해 근대화가 진행되면서 전통과의 간극이 급속히 벌어졌고 그에 따라 전통과 현대의 경계도 뚜렷해졌다. 그런데 70 년대 들어 편향적인 민족의식을 고양시키기 위해 현대 건축에 전통 양식을 직접적으로 차용하는 시도들이 팽배해졌다. 심지어 한옥의 지붕과 공포를 콘크리트로 찍어내는 기술까지 발달하기도 했다. 그러나 이런 시도들은 국수주의에 편향된 자기 만족은 있었을 지 몰라도 과거는 더욱 고립되고 현재와의 연결고리는 되레 끊어지는 결과를 초래하고 말았다. 어차피 전통도 진화하고 끊임없이 변화하는 것인데 현대와 접목시키는 시도들은 좀더 현실적이고 생동감이 있을 필요가 있다. 이번 기회에 양복 정장에 상고머리를 올리는 방식을 지양하고 세련되게 추상화 시킬 수 있는 방법을 고민하려 했다.

한편 이를 위한 조형 원리를 찾는 것은 또 다른 도전이었다. 전통 문양이나 형태를 가장해 크기만 키운 괴물이 되지는 말아야 했기 때문이었다. 좀더 근원적이고 보편적이면서도 고전미에 가까운 것을 찾고자 했다. 지구라트나 장군총처럼 좀더 근원적이고 원시적인 것에 최대한 접근함으로써 전통과 연결하려 했다. 다행히 전통의 직접적인 차용을 피하고 근원에 가까운 조형 언어를 찾으려던 시도들이 발주처에서 좋은 평가를 받았다는 점은 고무적이었다.

전체 연구소를 구성하는 세 개의 건물은 강당이 있는 국원관, 수장고 및 학예실 등 사무실 공간이 있는 중원관, 그리고 직원들의 기숙사 영역인 후생관이다. 규모는 각기 다르지만 모두 2 층이나 3 층 높이의 정방형 평면으로 구성되어 있다. 정방형 평면은 피라미드, 장군총 같은 묘나 석탑처럼 기념비적인 용도의 구조물에 많이 쓰인다. 그런데 이는 정작 우리가 자주 사용하는 건축에 적용하기 쉽지 않다. 그 이유는 규모가 큰 평면에 실들을 배치하다 보면 채광과 환기가 좋지 않은 방들이 어두운 중앙에 배치될 가능성이 높기 때문이다. 또한 주로 직사각형인 대지에 용적율을 다 채워서 계획하다 보면 결국 정방형의 평면을 적용할 수 있는 경우가 극히 드문 이유다. 중원연구소는 대지가 넓고 건폐율에 여유가 있을 뿐 아니라 채광을 필요로 하지 않는 수장고를 주 기능으로 하므로 정방형의 평면이 가능한 건축 유형이었다.

오랜 시간을 사무실에서 보내야하는 연구원들에게 좋은 사무 환경을 제공하기 위해 각 층마다 주위로 돌아가는 테라스를 계획했다. 넓은 터에 지어지는 연구소임에도 2 층이나 3 층에서 일하는 연구원이 바람을 쐬기 위해 1 층까지 내려가거나 옥상에 올라가야 한다면 불편하다고 생각했다. 한 두 층 오르고 내려가는데 무슨 큰 문제냐고 할 수도 있지만 분명히 이로 인해 번거롭게 되고 그러다 보면 결국 답답한 실내에서 하루 종일 시간을 보내야 하는 경우들이 생긴다. 마치 공원에서 일하듯 답답한 사무실에서 언제든 밖으로 나가 바람 쐴 수 있는 자유를 제공하고 싶었다. 흡연자들도 눈치 보지 않고 바깥 공기를 쐬며 담배 한대 피우고 다시 업무로 복귀할 여유를 갖기 바랬다. 아쉽게도 애초의 계획처럼 다양한 수목들로 채워지지는 못했지만 각 층의 사무실 주변을 돌아가는 잔디밭 테라스는 예상보다도 훨씬 더 호응이 좋았다. 밤낮과 주말도 없이 연구에 매진해야 하는 학예사들이 잠시 쉬는 쌈지 공원이자 환기가 필요할 때 문을 열기만 하면 시원한 바람이 들어오니 금상첨화다. 딱딱한 문화재 연구소에서 일하는 직원들에게 다소 숨통을 틔워주는 공간이 된 것은 가장 큰 수확이었다.

Jungwon refers to central region of the Korean peninsula that encompasses cultural identities of 3 ancient kingdoms of Korea- Shilla, Baekje, and Goguryeo- as it was a highly coveted and sought-after area. Design competition was held after it was decided to establish a research center dedicated to excavation, research, and preservation of cultural relics and artifacts in 2010, and poly.m.ur was awarded the project.

In addition to the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, Jungwon National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage would be the 6th national research institute of cultural research in addition to institutes already in place in Gaya, Gyeongju, Naju, and Buyeo. With an exception of the institute in Gyeongju, which adopted the design of traditional Korean roof, all other institutes were presented in a form of modern architecture. As they embarked upon the project of establishing the newest research institute, the Cultural Heritage Administration of the Korean Government was fully aware for the need to embrace Korea’s unique cultural identities to the design of architecture. Architects working in Korea know well the risk associated with attempts to bridge the past and present, and we also understood the challenge of defining an identity that translates the course of history into an architectural narrative with modern-day relevance. But it was a challenge that I had to take on; gladly and willingly. How do you define Korean architecture? Can the identity of Korean architecture be defined without adopting associative forms? I began the project by contemplating ways that would allow me to pursue abstract approaches to the design without having to resort to cliché characteristics such as patterns, colors, or styles. Korea’s rapid modernization is characteristically powered by foreign forces and resulted in rapid departure from the past with a clear division between the past and the present. When a manic wave of nationalistic movement swept the country in the 70s, architectural world responded by making literal adaptation of traditional forms to modern architecture. It was during this time when technology to churn out concrete tiles and capital for traditional roof designs was developed. Such attempts may have satisfied the nationalistic fever but ended up widening and deepening the gap between the past and present to a degree that the link was eventually severed. Like history that never stops and continues, tradition also evolves and changes. Therefore, attempt to embrace tradition should consider relevancy and vitality from modern point of view. I took this project as an opportunity to resist the urge to go on the same route of making literal adaptation of tradition as it would be like insisting traditional hair-style for a man dressed in suit. My sight was set on abstract and sophisticated interpretation of the Korean heritage. Next challenge that awaited me was figuring out the formative formula of my design vision that refused to create a colossal atrocity that pretended to embrace traditional shapes and forms. As I explored inspirations that were more fundamental and universal while being true to traditional aesthetics, idea of fundamental and primitive architecture such as ziggurat of ancient Mesopotamia and Janggunchong (Stone Tomb of General) gained strong support as an effective bridge to the past. Fortunately, my effort to come up with a formative narrative that focused on primitive inspiration without having to rely on superficial adaptation of cultural heritage was well recognized and received by the client.

The complex is designed to house 3 separate buildings: Gugwongwan with an auditorium, Jungwongwan with office spaces including storage and research facility, and Husaenggwan as dormitory for staffs. Varying in sizes, but each building adopted square shape for floor plan featuring 2 or 3 floors in height. Square floor plan is typically seen in monumental structures such as tombs – pyramids, Janggunchong, etc. - or stone pagodas. Its real-world application is limited, because it becomes inevitable for rooms placed in the middle to have limited access to light and air as more prominent rooms take the priority space near windows. Also, most properties are divided in rectangular shapes and effort to maximize the floor area ratio almost automatically rejects the concept of square-shaped floor plan. Application of square floor plan was possible for the Jungwon National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage because of 2 factors: generosity in the site area and applicable floor-area ratio and usage as storage space that didn’t require access to natural light.

For the main building of Jungwongwan where researchers were hard at work for long hours, terrace that encircles 3 sides was placed on each floor as an enhancement of work environment. Building wasn’t tall and it was only a floor or two to get fresh air from the ground floor or roof top, but it still didn’t seem unnecessary as long as there was enough space for alternative solutions. Outdoor space on each floor would be more effective in motivating the staffs to take the rest they need as it eliminates the trouble of leaving their floor. With such easy access to an outdoor space, there would be no excuse not to take advantage of the benefits and staffs could easily step outside and get fresh air as if their office is surrounded by a park. Smokers, in particular, would appreciate the layout. Original design of the terrace featuring a wide variety vegetation met with a setback and resulted in a more simpler landscape, but reception for the terrace garden was much more positive and enthusiastic than anticipated. Researchers were working in an intense environment often involving long hours and stressful situations, and they truly appreciated being offered an easy and simple access to fresh air just steps away from their office. Being able to create a space that was essential for the comfort and respite of researchers and staffs working in a rigid environment break was the biggest accomplishment of the project.